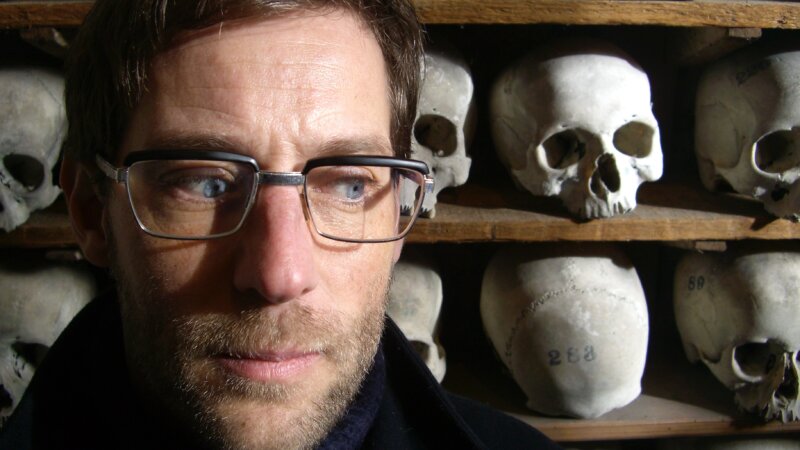

Simon Heywood: South Yorkshire Folk Tales

Simon Heywood is a storyteller, songwriter, folklorist and lecturer in storytelling and creative writing at Derby University. With a long back catalogue of performances and workshops, including a fascinating project giving voice to the conscientious objectors of the First World War last year, Simon has an interest in the rejuvenation of half-forgotten history and folklore tales. His new book, South Yorkshire Folk Tales, was co-authored with Damien Barker. As the name suggests, it documents some of the lesser known local tales and will be published by The History Press later this year.

South Yorkshire Folk Tales is out in autumn. Tell me about the writing and researching of the book.

Well, Damien (Barker, my co-author) turned up in one of my creative writing classes a few years ago and started telling me about Firbeck Hall and the Green Lady. It's near his family home, and so is Roche Abbey, which also has many stories and rumours attached to it. I'd lived in South Yorkshire for getting on for 20 years, having grown up down south, and I'd never heard the story of the Green Lady, or anything like it. It struck me at once, and it made me think there might be more of these stories around than I might have assumed.

The History Press have been publishing books of folktales and legends, county by county, and Damien and I contacted them about writing a book for South Yorkshire. We briefly considered covering Yorkshire as a single county, but I didn't want to do that. It was too big, and also too easy in a sense. If you look in all the major folktale and legend collections on Yorkshire, most of the better-documented stories tend to come from further north in the county. If we narrowed it down to South Yorkshire it would make us dig deeper and look harder for those hidden treasures.

It worked. We talked to friends and family and looked round local studies libraries and archives, and did a certain amount of research online. We came up with a lot of stories that we had little or no idea about, and having shared them about a bit with people who know the area well, we think there'll be something new for everyone in South Yorkshire Folk Tales. It's transformed my view of South Yorkshire's landscape and stories, and storytelling generally, and I just hope we've managed to communicate some of that sense of discovery and excitement in the book.

How much reinterpretation have you done with the tales? Given the fluid nature of folk tales, and as a storyteller yourself, is it important that you place your own stamp on them?

We've ended up doing a fair bit of reinterpretation. Not all the time though. We've tried to be clear when we've done what, so readers know when we're giving them the unvarnished story as we found it, and when we've given a creative interpretation. We've tried to do everything sensitively. A lot of the time you find the stories in their original form seem a bit garbled to modern readers. A lot of the early Robin Hood stories, for example, are set up and down the A1 around Doncaster - the Great North Road. The original ballads were composed for audiences in their own time and place. The assumption is that the listeners already know how to shoot a longbow, where the blackspots are for highway robbery on the A1, how to negotiate a payday loan with the local monks, and so forth. Most of that knowledge is now lost and forgotten, so you have to fill in the gaps to make the same story feel real today.

Which stories in particular jump out as your favourites from the book?

There was one story from Sheffield, which was written down by a local author, Joseph Woolhouse, in the 1800s. He learned it from his grandfather, who knew the people involved. It's the story of a man who was walking home from Sheffield towards Kelham Island one evening when he became convinced he was being followed by a demon - a barguest. To get away from the barguest, he cut across the field which is now Paradise Square. It was called Hick's Stile back then. He hacked across Hick's Stile, and made it home in one piece in the end, after several adventures. After I found that story, I went to have a look at Paradise Square, and, of course, there really is a pathway cutting diagonally right across the cobblestones, leading straight onto Silver Street Head. It's all paved and painted out now, but it really does look pretty much exactly like the route you would take if you were trying to get away in a hurry by cutting the corner of Campo Lane and Lee Croft. You'd hardly notice it, unless you knew the story, and the story isn't so widely known nowadays. It all felt very real for a moment.

We had a few moments like that. We were on a bus, trying to find a place near Tinsley where a great Dark Age battle supposedly took place, in the shadow of Meadowhall. At first, we thought this story was forgotten by everyone but historians, but we got talking to all the shoppers going home on the bus to Darnall, and a good few of them knew about the battle. When we got off, the whole bus was still deep in discussion, trying to remember the names of the kings.

If you come at these stories from the outside, with your ideas shaped only by what you find in books, it's easy to fall into the habit of thinking in terms of the ‘lost legend’ or ‘forgotten folk tale’ of this place or that place. But in my experience, legends and folk tales aren't always as lost as they might at first appear. The memory and the imagination of the stories is still very much alive. That's a really exciting thought. If the book helps to keep the stories alive, then that really is mission accomplished. It wouldn't have to be the greatest book in the world - if it whets people's appetites a bit and gives them something to talk about and listen out for, it's done what it was designed to do.

Does a lot of what you do amount to historical research and translation?

Yes, in a nutshell. It's about trying to write them in a way which communicates the excitement of finding them. That's translation of a kind. There's a bit of actual translation involved if you get a medieval poem or ballad. Medieval English is like a foreign language, and you have to basically rewrite it from scratch in the English of today.

Do you find that some stories are better spoken than written?

It's a case of swings and roundabouts. But telling stories aloud is a useful waffle filter. Everything I write I try to read aloud, and if it's a decent story it helps to tell it a few times before trying to commit it to paper. I don't always write down everything I tell aloud, though.

You did a Halloween ghost trail last year in the General Cemetery. Are walking tours something you want to explore more in future?

Yes, I really would. I'd like to do the less obvious places as well. It's not hard to imagine spooky things happening in an old cemetery, but I would love to go round some city centres and say things like, “This is where the man ran away from the demon in 1700,” by the convenience store on Campo Lane in Sheffield. Or go out to Rossington and say, “This is where the ghost of the black cat appeared on the grave of the Gypsy King.”

Do you see a distinction between your work as writer, oral storyteller and musician, or are they just different ways to spin a yarn?

Ultimately a story is a story is a story, but there are differences in the way you put it over. When you write you only have the words. There is no chance to pause or leave a silence, or use a gesture or a facial expression, or a particular tone, so the words have to work harder - the language has to do all the work. Some people are better at one thing than another. I'm pretty wordy by nature so I quite enjoy the writing. I think in some ways you have more freedom as a writer as well. If you write a joke and readers don't find it funny, that's not as agonising as telling a joke and nobody laughing. So it's easier to take risks in writing. Maybe it's too easy...

simon-heywood.com )