High Tech Soul: Transatlantic industry

Techno always used to puzzle my former self. How could millions across the world be entranced by what is essentially a straight 4/4 beat repeated into eternity? That coupled with the clichéd image of a hedonistic German man pumping his fist in the air with unbridled enthusiasm left me wondering what all the fuss was about.

Recent years have led me on a journey through music - electronic in particular - that has resulted in a stream of ever-enlightening discoveries. Sun Ra has convinced me that space is indeed very much the place and bands like Zs and Can showed me the sonic potentialities of an often uninspiring conventional rock set-up. However, maybe the most profound change concerns the genre that I could never get my head around - techno. Whilst the oft-familiar sight of a partying European isn't too far-fetched - Germany is of course one of Techno's greatest producers - the story of the genre's rise to prominence is much more ideologically substantial.

The development of the techno sound can be almost entirely attributed to one man - Juan Atkins. As a young music enthusiast living in the suburbs of Detroit, Atkins was exposed to copious amounts of protoelectronic sounds. Radio DJ The Electrifyin' Mojo is almost solely responsible for this exposure, providing the whole of Detroit's white and black youth with a soundtrack to their weekends. He seamlessly blended the mechanical sounds which were being produced due to the advent of synthesisers by the likes of Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra with the interplanetary funk frequencies of George Clinton and Prince. Mojo provided a musical collage that was so interracial through its blurring of the lines between white and black music that he managed to create an audience that was free from many of the racist undertones seen in previous decades. For Atkins, it was this mix of futuristic technology and soul that formed the conceptual basis for his music and, spurred on by the futurist writings of Alvin Toffler, he started producing electronic sounds with friend Rik Davis under the moniker of Cybotron. During this time, he worked constantly with school friends Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, teaching them the basics of music production and DJing and they soon became the vanguard for this new electronic music, which we now know as techno.

The sound itself was one that was clearly a product of Mojo's audio cocktail - the industrial mechanics of Kraftwerk permeating through a layer of synth chords and funky basslines, reflecting the soul of black American music. This along with the clear influence of Chicago House with its repetition and gradual development of melodic themes meant the genre was clearly a sound of its own. However, what made techno special was its ability to translate the sound of Detroit as a city. As a former industrial giant, the monotony and repetition of the factory lines was a constant soundtrack to most working class families whose members would be working in the industry on a daily basis. Most think of the sound of early techno as being an ode to this lifestyle - a nostalgic reminiscing of the industrial glory days through the replication of the sounds of the motor factories. However, this views the industrial days with a sense of naïve nostalgia, which fails to account for the conditions of the working man at the time.

A similar if smaller scale techno development was happening in the latter years of Detroit's rise to prominence much closer to home. Here in the Steel City - a name of course also attributed because of the city's industrial history - early synthesisers were making waves thanks to the likes of Cabaret Voltaire and The Human League. These sounds were mechanical and cold, undoubtedly a reflection of the city's factories and steel works. In the late 80s, as sounds from the US started infiltrating the North's clubs, the imported Chicago House approaches were being fused with the already-established Sheffield 'industrial' sound. At the helm of this innovation were the trio Forgemasters, consisting of production whiz Rob Gordon - a man responsible for honing the sound of many of Sheffield's finest musical stars at the time as well as being one of the co-founders of Warp Records - DJ Winston Hazel and friend Sean Maher. Hazel was renowned in Sheffield for his beloved club night Jive Turkey, which united races in a similar way to what the Electrifyin' Mojo had done a decade earlier in Detroit.

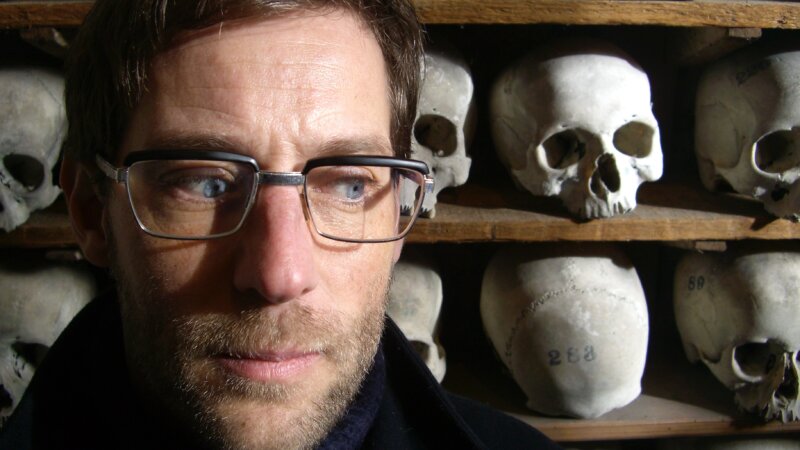

This group's output, whilst limited, formulated a new and wholly electronic sound for Sheffield, and their first release 'Track with No Name' also happened to be the debut release on Warp Records. I caught up with Gordon and Hazel in April to learn more.

Rob explained the atmosphere of Sheffield at the time as being: 'hard, cold, broke, aggressive. There was a lot of tension, a lot of anger and everything was just hard. Not much changed, so you get this sort of repetitive nature of stuff just going on and on and on. If you listened to the Detroit music at the time, it had the same atmosphere - it was the hardness. They were talking about the same things in their lives even if it was just through music. Musically, we were illustrating similar surroundings.'

The hardness of Sheffield at the time unconsciously fed into their productions, which fused the house music sounds that took up a significant place in Winston's DJ sets with Gordon's passion for reggae and the soundsystem culture it entailed. Prioritising bass and a diverse range of audio frequencies, Gordon brought a new perspective to the house template, which he felt 'sounded like someone was doing it on cassette at home'. His motivations during production were clear: 'the drums on 'Track with No Name' were the same drums I had played for a reggae band years earlier - like this dub sort of stuff. It's following the same kind of patterns if you listen to it. I thought: 'Oh you could put a beat like this because at the end of the day if I heard a house record with a reggae beat like this, I'd think it was good.' Gordon's hostility to house sounds allowed the group to freely traverse the tedious genre stylings that he felt many of the US imports exhibited. Once again the fusion of black soul music - this time with a distinctly Afro-Caribbean tint - with repetitive house progressions occurred to produce a sound that distinctly exhibited the essence of its industrial birthplace.

'One of the sonic things in Sheffield that's a subliminal baptism of techno fire was in the foundries, they used to have these massive hydraulic hammers and because they were only in the Don Valley, the sound used to ricochet up the valley and hit all the hills and then dissipate out so you had this amazing sonic experience. It happened in the morning, in the afternoon and at night. It reverberated to a point where it affected the air presence in the city. You could feel the pressure change and depending where you were you could even feel it in the ground. These were incredible sonic experiences growing up as a child. We were completely oblivious to it until we listened back to the music we produced and thought: 'Oh my god, that's why everything was so clonky and bassy.' It had a massive effect on how electronic music developed in Sheffield.'

The music that Forgemasters and co produced quickly became labeled 'bleep techno' with a sound that distinctly reflected the city's industrial landscape. Warp went on to replicate further successes with the curation of all kinds of electronic music, but it is these roots - an identity, which for many, especially Gordon, was distinctly black in origin - that many hold closest to their hearts. A fortunate by-product of the once flourishing but now disappeared times of industrial splendour, techno endures as a testament to the way in which the world affects human expression. )