Why isn't Sheffield more ambitious? Here’s six ideas the city could steal from other Labour-led councils in 2024

Ambitious local leaders are pioneering new ideas ranging from citizen financing for the clean energy transition to radical new approaches to housing.

With only one Conservative councillor out of 84 in the chamber, Sheffield should have a supermajority for ambitious, radical change. But despite the city's history of experimenting with innovative new ideas, the Council has not been seen as one of the UK's more forward-thinking local authorities for a long time.

At the same time, other (mostly Labour-run) councils are experimenting with new ideas to tackle the systemic problems that are common to cities across the UK – whether that's in response to the climate crisis, inequality, or the way poor public transport fragments and isolates communities.

Here are six of the most exciting ideas that are being pioneered in UK cities – all of which could be applied to Sheffield.

Warrington: Municipal climate bonds

Hundreds of towns and cities including Sheffield have declared symbolic climate emergencies, but they mean nothing if the money isn't there to take any action. Unfortunately for cash-strapped councils, the urgent need to take action is dovetailing with a crisis in local government funding.

Labour-run Warrington Borough Council have managed to sidestep the government's deliberate underfunding of local authorities by raising money directly from residents to fund renewable energy projects. In 2020 members of the public were given the chance to buy bonds for as little as £5 and get regular returns on their investment, with the money used to fund low-carbon projects in the town.

The

council partnered with ethical investing company Abundance to raise

£1 million from 500 investors. This was used to build a 23 MW solar

farm with 40 MW battery storage, which not only met the local

authority's entire energy needs but also allowed them to sell surplus

energy back to the grid to repay the initial investment.

All of this

happened without needing to raise any money through Council Tax –

an unfair tax that is disproportionately levied on the least

well-off.

Oxford and Liverpool: Landlord licensing

You don't have to be a private renter to know that Sheffield has a landlord problem.

A few months ago, the Sheffield Tribune reported on Gary Ata, the new owner of the Old Town Hall, who a local councillor described as running a company with "a track record of being irresponsible in their obligations to both their residents and the wider community". Despite the council actually prosecuting Ata twice, there's nothing to stop him continuing to lease out property to tenants in the city.

If you want to throw a street party or sell food to the public, you need a license. But you don't need a license to lease out somewhere to live – except if you’re a landlord in Liverpool or Oxford. In both cities (Liverpool is Labour-run, Oxford is no overall control), any prospective landlord needs to prove that they meet a whole range of safety and wellbeing standards before renting out property.

Until October last year, Sheffield had a much smaller, targeted

scheme that aimed to address the especially poor and dangerous

quality of rented homes around London Road and Abbeydale Road. But

this scheme, only intended as a temporary intervention, has now come

to an end. Organisations like local tenants union ACORN would like to

see Sheffield apply to the government for a permanent city-wide

scheme, as part of a strategy to improve the dire quality of the

city's rented housing.

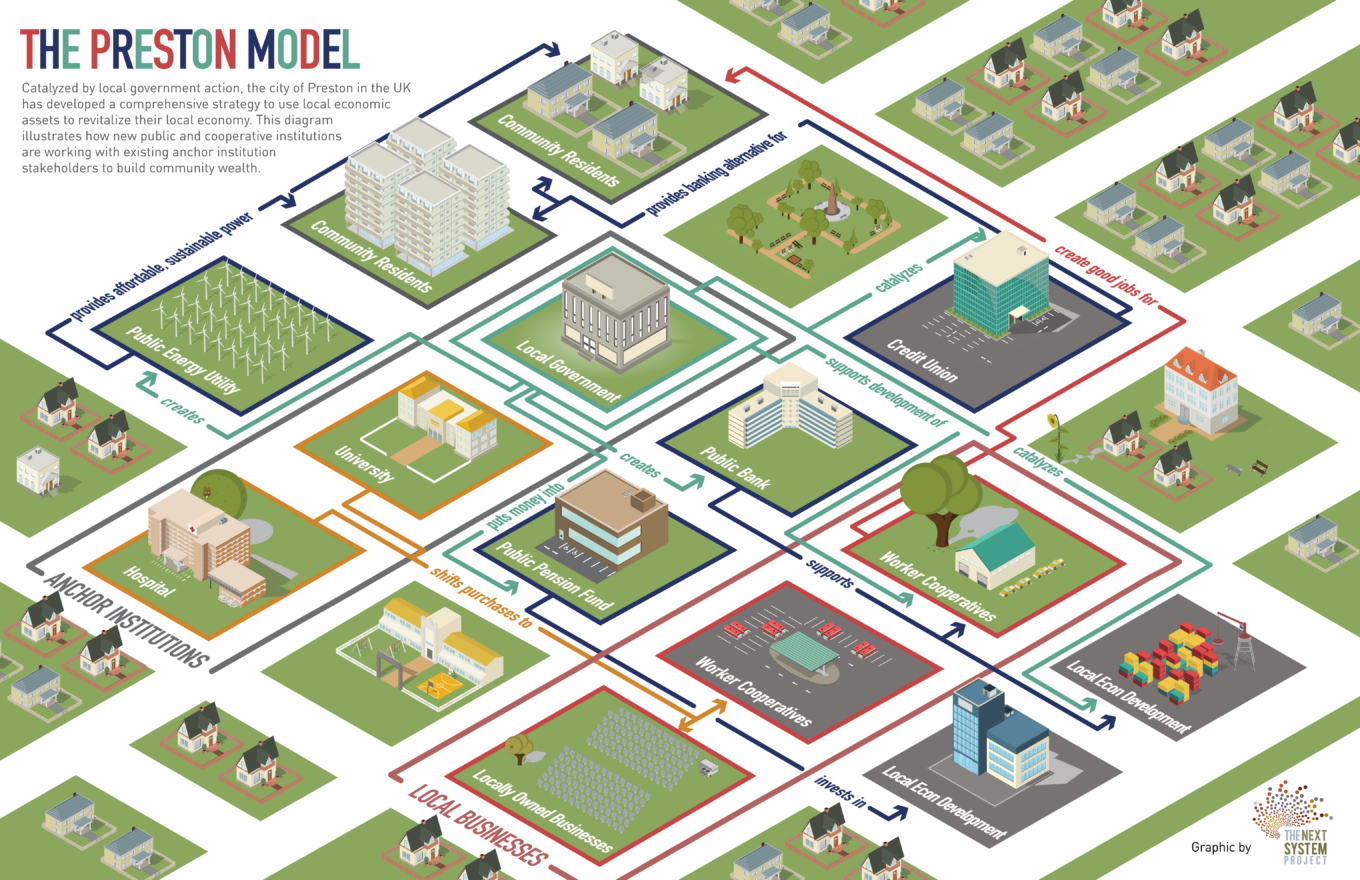

Preston: Community Wealth Building

The risks of outsourcing to large multinationals are unusually well-known in Sheffield. Many believe that the epic battle over the city's street trees can be traced back to a decision to outsource street maintenance services to engineering giant Amey, owned by two private equity firms. The company have little stake in Sheffield, and the (enormous) profits made on the Streets Ahead contract are spirited straight out of the city – and will be until 2037.

Is there another way? Labour-controlled Preston Council are the standard-bearer for the idea of Community Wealth Building (CWB), which aims to keep as much money within the local economy as possible. This is partly done through changing the approach to outsourcing.

Every big town or city has a number of 'anchor institutions'. These are organisations that are intrinsically tied to that place and that can't easily leave (for example, Sheffield City Council, Sheffield United and the University of Sheffield are unlikely to move out of the city). The trick is working with all the anchor institutions in a particular city to come up with an agreement to change their procurement rules to prioritise local firms – even if they're more expensive than using a multinational like Amey.

The idea is that even if they end up paying a little bit more for specific services, the anchor institutions then benefit from being part of a stronger local economy and a more thriving city. This has obvious benefits for both local councils and NHS trusts, who could potentially save money on poverty-related healthcare costs while improving local citizens’ quality of life.

For far too long Wandsworth has seen private development delivering very low numbers of social housing. We are looking to change this through our planning rules pic.twitter.com/VxfUSPWhpm

— Aydin Dikerdem (@AydinDikerdem) November 26, 2023

Wandsworth: 1,000 council homes

The south-west London borough of Wandsworth have a strategy to build over a thousand new homes on unused patches of council land, known as infill development. This in itself is impressive, in an era where the Right to Buy followed by strict spending rules have decimated the ability of councils to build their own housing. But under the original plans, 60% of these homes would have been sold off to the private sector, with only 40% remaining as proper council homes.

But at the 2022 local elections what was once “Thatcher’s favourite council” changed to Labour hands, and in came Aydin Dikerdem, a young new cabinet member for housing who like many of his new colleagues had previously worked on housing and renter campaigns. The old plan to use council land, assets and know-how to bolster the private sector was thrown out. Soon after the election, Dikerdem switched the scheme to deliver “100% council rent homes on council land”.

“Given how rare and valuable public land in London is, we think it’s important that... we try to protect public land for generations to come,” he told Inside Housing. He also put a stop to a policy that saw the council sell of their most valuable homes to fund cheaper purchases elsewhere, after discovering that many of the homes sold off were bigger properties that were needed by larger families on their waiting list.

Sheffield has more potential infill sites than most cities, whether it’s the former factory sites stretching out towards Meadowhall or the still largely empty sites surrounding Kelham Island. The council also owns an unusually large amount of the land.

A new tram route in Nottingham was mostly funded through a Workplace Parking Levy.

Alan Murray-Rust on Wikimedia Commons.Nottingham: Workplace Parking Levy

Sheffield's Supertram network operates with the same three lines it opened with in 1994. Yet Nottingham's NET tram, which was built ten years later, already has a shiny new line that doubles the size of the original network. Why? Part of the answer lies with the city's Workplace Parking Levy (WPL), which the Labour-run council say funded the second tram line almost entirely.

The WPL is a charge that applies to any employers with eleven or more workplace parking spaces in Nottingham city centre. The cost per space is currently £522 a year (it's up to employers whether they pass this cost on to their staff or not). The aim of the charge is two-fold: it's partly to nudge employees into making more sustainable travel choices, but it also provides ring-fenced funding for public transport and active travel projects across the East Midlands city.

Aside from the tram line, the WPL has helped pay for new cycle paths, 200 electric vehicle charging points, and a new electric taxi fleet. In Sheffield, the local Green Party have long pushed for our own WPL, but nothing has actually happened so far.

🏡 This morning Andy launched the consultation on the Greater Manchester Good Landlord Charter.

— Mayor of Greater Manchester (@MayorofGM) January 8, 2024

The first of its kind in the UK, the charter seeks to improve the standards of homes in social housing and the private rented sector.

Find out more 👇https://t.co/NFpAKJKz34 pic.twitter.com/9Ah0RzNt07

Greater Manchester: Housing First

Sometimes the most obvious solutions are the right ones. Generations of politicians have spilled ink over how to tackle the UK’s homelessness problem but have rarely mentioned the most straightforward answer: just give people homes. Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham is looking to Finland where, as he told the Big Issue, the principle of ‘housing first’ is a “national philosophy” rather than just a project.

The principle says that improvements in almost all aspects of

people’s lives, from health and wellbeing to education and career

prospects, have to start with housing – that having a good, secure

home is a prerequisite for a decent quality of life.

In Manchester, this has led Burnham to launch the Housing First programme, which offers safe and secure accommodation to people with long-term experiences of rough sleeping. Combined with support, the permanent nature of the accommodation gives people a platform from which they can start to rebuild their lives and reduces the likelihood that they will end up back on the streets. So far, 375 people have been helped into secure accommodation with more than three-quarters sustaining their tenancies – a much higher success rate than other anti-homelessness projects.

Next he plans to work with the councils that make up Greater Manchester to transform the region’s private rented sector, which like in every other major city is a major source of insecurity, poverty and ill health. If it goes through, the Good Landlord Charter would require landlords to sign up to a set of minimum standards for their rented homes. If they fail to meet the requirements, local councils will look to use compulsory purchase orders to take properties away from them and turn them into high-quality social housing.