From Berlin to Belgrade, only one sound could heal a fractured Europe in the 1990s

As European communism fell apart, forgotten basements and Stalinist ministries played host to new rituals of unity and escape.

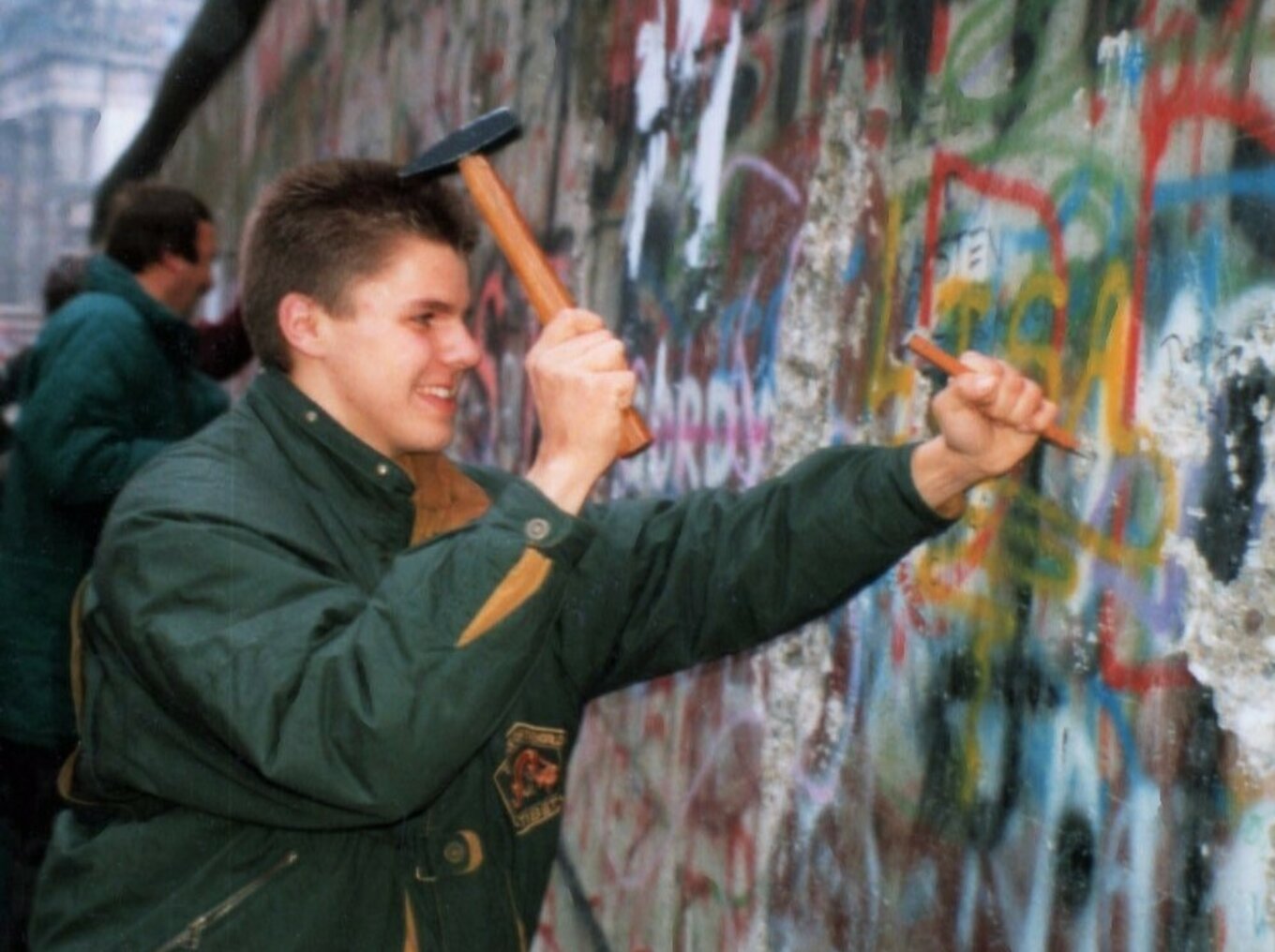

West German Andree Werder at the Berlin Wall in November 1989.

Werdersen on Wikimedia Commons.

Rave music has always been transitional. The genre was a radical

development in sound from pre-nineties dance: synth-pop first removed

the human from dance music with drum machines which outmoded the live

percussion of disco. But it was rave, with its entirety of electronic

samples, that finished the job.

Rave was also always

competing against itself to reinvent. This was noted by the late

music theorist Mark Fisher in Ghosts of My Life. Rave mutated

with such speed and individuality that its sub-genres – hardcore,

jungle, techno, trance – sounded comparatively alien. Rave

maintained, as Fisher puts it, a degree of “future shock”.

But by ‘transitional’, I also mean that rave became popular in the decade where Europe transitioned out of two oppressive regimes. First, the USSR dissolved after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This forced a divided city to patch up years of angsty divide. Second, Yugoslavia struggled on a while longer. The majority of member states jumped ship by 1992, not without ruinous conflicts, leaving only Serbia and Montenegro left until its 2003 dissolution.

It was rave that nursed, if not mended, Europe’s soul after these

years of fracture. And only a genre of music as transitional,

optimistic, and inventive could have had such success. Its

forward-thinking drive was just what the continent needed at the

time.

Glitter with rust

Felix Denk and Sven

von Thülen’s oral history of the Berlin scene, Der Klang der

Familie, illustrates how rave mended the fractured city. Rave,

the pair say, inspired togetherness, and by extension, hope for a new

future. Another speaker, DJ Tanith, recalls: “Everything was slowly

migrating. No-one was interested in the west anymore”. The east was

a brave new world of cultural opportunity as young Berliners

reunited. “Old public buildings [and] former ministries in

Stalinist architecture” were all up for grabs says Johnnie Stieler,

co-founder of Tresor.

Tresor, now one of

Berlin’s most notorious clubs, found its first home in such a

building. The disused bank even peered out onto the ruins of the

Wall, and the view reminded the club’s revellers of the concrete

island half the city had once been.

The bank’s old vault contained safety deposit boxes and lockers that “glittered with rust”. The resourceful new owners were attracted by the decaying landscape. “The space dictated the brutal sound” at Tresor, one former DJ recalls. Marathon parties of hard-hitting techno mirrored the brutality of east Berlin back at itself.

Tresor’s parties dreamt up a new future which reunified youths from

both sides of the Wall. From the east came football hooligans, punks

and breakdancers. The west brought trendy artists, squatters and

furloughed British soldiers. “Techno”, say Denk and von Thülen,

“called for participation, [or] a sound of flat hierarchies. Not

for nothing was it referred to in the early days as a music with no

need for stars”.

Its pounding,

anarchic energy attracted misfits from both sides of the Wall. The

diminished importance of identity saw unlikely friendships become

commonplace. “Everything was focused on the music and the new

togetherness on and alongside the dance floor,” write the pair.

“The exuberant, contradictory community that converged there every

weekend really saw itself as a family.”

A reality of

togetherness

Yugoslavia, much

like the USSR, was beginning to disintegrate at the start of the

nineties. The Yugoslav People’s Army attempted to keep the alliance

together by waging disastrous wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The

international community responded by sanctioning Yugoslavia. And

internally, pacifist protests spread in cities like Belgrade, then

the Yugoslav capital, as young Serbs found themselves pitted against

the government and their neighbours.

Belgrade tore apart at the very moment Berlin crashed back together. Both cities were dealing with upheavals which gave rise to fundamental questions of identity and nationhood. And like in Berlin, rave played an important role in unifying Belgrade and providing hope for the future.

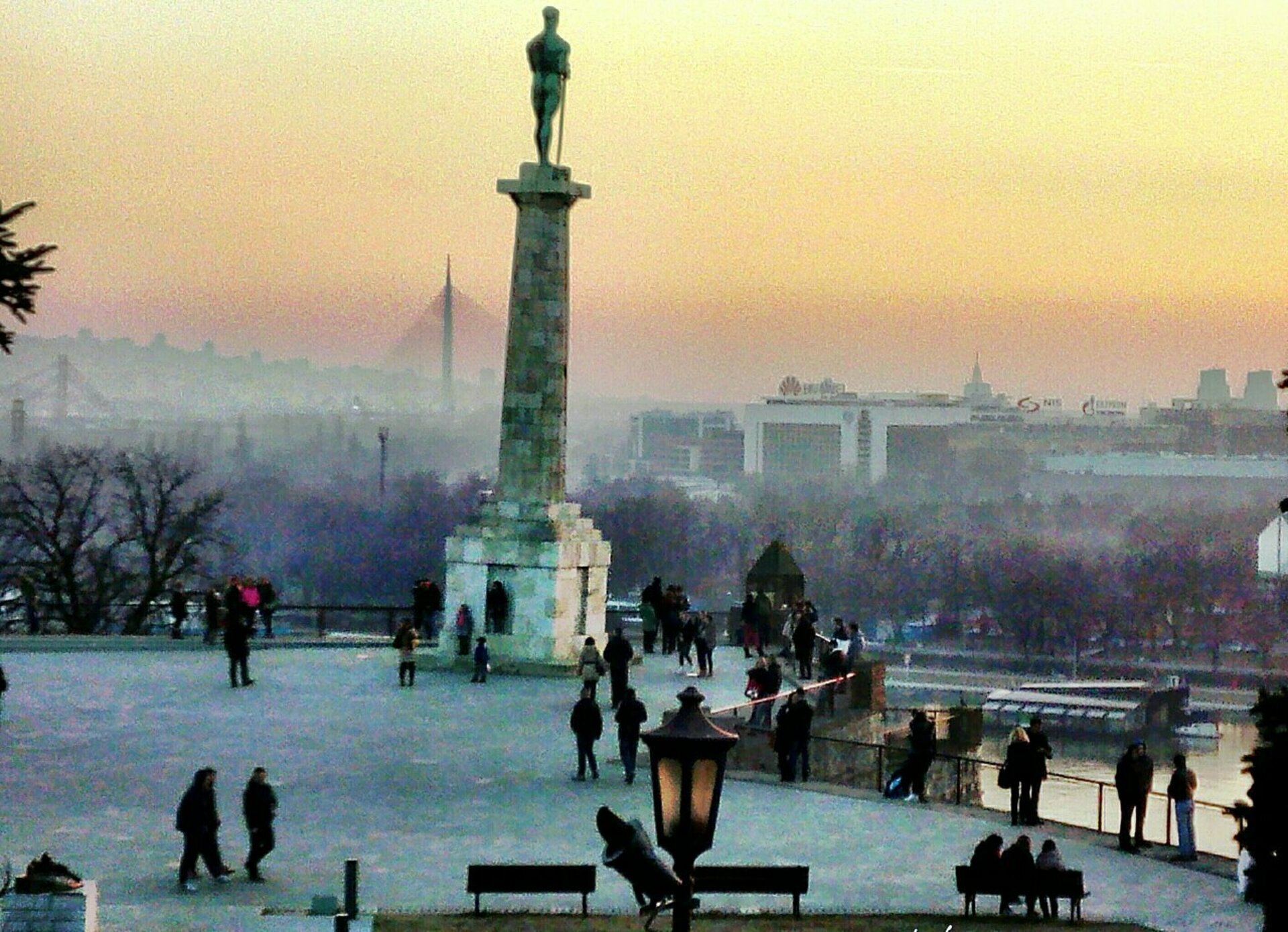

Belgrade at sunset.

Надица Гавриловић on Wikimedia Commons.

“It all started in 1994 when the iconic Klub Industrija opened in

downtown Belgrade,” local DJ Hypnotic explains to me over email.

“The rest is history. I was a kid with a great passion for music. I

went to my first techno and trance party in that fateful 1994, when I

was 13, but I was a lone raver in my elementary school, and I didn't

go out as much as I wanted to. I had no-one to go with. I didn't even

manage to enter the club every time because I was so young. I was

totally into it, and I couldn't understand why they sometimes

wouldn't let me in. Anyway, Industrija was the most important place

for the Belgrade youth, where we could escape and forget for a moment

about the horrors of the outside world.”

At the same time, Hypnotic acknowledges that escapism was not the primary motivation behind the scene. Sanctions had cut Belgrade off from the world, but rave proposed an alternative reality of togetherness. “We lived the rave with all our heart and soul,” Hypnotic tells me. “The troubles on the outside only brought us closer together. We couldn’t travel that much, but others could come to us. We had foreign DJs playing every other weekend, and enough domestic ones to keep the scene alive. Actually, that’s an understatement. The scene wasn’t just alive, it was big. One of the best in Europe at the time. But it was hard for DJs and rave fans to get the music given the circumstances. This meant we were all very passionate about the whole thing. We shed blood, sweat and tears for every track, every record.”

Young Belgradians hunted for records, socialised, and brought some

order into the chaos of their lives. Many found comfort in the stable

routine of browsing, buying and cataloguing record collections. Just

as much as it brought about togetherness, rave became a pillar of

stability in the war-torn capital.

Music’s space

age

Hypnotic later

uploaded his record collection to YouTube under the name

‘2trancental’. The majority of it falls under the category of

early to mid-nineties trance. The sci-fi bliss of the music belongs

to the same airbrushed world as the 3D art of nineties rave flyers.

“Some of the most popular tracks from my channel have already

received reissues, like Nail’s ‘Cassiopeia’ and Berkana

Sowelu’s ‘Solid Fuel’”, says Hypnotic.

“Trance encouraged

the depths of feeling, states of mind and passion we needed to

explore both the inner and outer worlds. It was the space age of

music, driven by the pure love and excitement of discovering

something new. It involved both a mystery and a freedom of spirit, a

medium to transcend everyday reality. The music just had that

hypnotic element and quality to lock you into a trance. Those were

amazing days of such hope and rising consciousness.”

Hypnotic preserves this essence of trance with his YouTube channel. “I started it out of despair lol”, he admits, “because it was a bad time for anything old school. I had tried to find certain tracks online and realised there’s so much missing. I couldn’t just watch everything die and disappear – it was my life.”

“I thought that with a little luck, over time, I could gather

fellow ravers in one place. Somewhere to listen together and

reminisce about the old days. It turned out much better and bigger

than that. New generations got involved, and I'm so happy about it,

because it gave me hope that it wasn't all over yet.”

As of 2024

Hypnotic’s channel boasts 60,000 subscribers and over a thousand

uploads. Its value lies in its introduction of an obscure subgenre,

the feeling of the ‘old school’, to a new generation of ravers.

The comment section became a go-to for trance fans online. This

humbles Hypnotic: “I keep getting messages from fans, DJs and

producers from all over the world. They tell me how much they love

what I do with the channel, how it has inspired them to start

discovering, making their own music and DJing. They send me tracks,

mixes and records they have released.”

“More and more DJs

are including old school tracks in their sets, and many other old

tracks are getting reissues, so the wheels are turning.”

Back to the

future

Disaster struck in 2020 when scammers hijacked Hypnotic’s Gmail and the channel was suspended. “It was a classic example of phishing”, he explains, “I was careless, and clicked on something I shouldn't have. This was a dark and tense period for the channel, but with the great support of my fans, we got Google to solve my case.”

Hypnotic took a step back in the wake of the channel’s close call,

and reconnected with an old friend from Belgrade. “I felt it was

the right time to give some of his music a vinyl release. It would be

the first real old trance from 1994 to be released on wax in modern

times, and could inspire others to start exploring that kind of sound

again. All in the hopes of triggering a true comeback.”

That EP, Lake

by InnVision, was released on Tunnel Vision Records in 2021.

‘Lake’, the A-side, brims with 13 minutes of euphoric arrival. On

the back, ‘Nighty’ works with the same buoyant optimism but the

broken beat caters to the chill-out room rather than the dancefloor.

Virtual communities like Hypnotic’s keep the unifying essence of rave alive, now more than ever. A study of Berlin and Belgrade’s rave cultures should serve as a blueprint for how we can navigate geopolitical upheavals today. Rave is not just a genre but can also be a tool – a proactive way of combating apathy for a future which can at times look bleak.