"I’m fascinated by art and science’s shared ability to record the transient"

Sheffield’s rivers are at risk of pollution from old coal mines – and a boundary-breaking collaboration is using art to show how.

Environmental chemist Rachel Schwartz-Narbonne working in the lab.

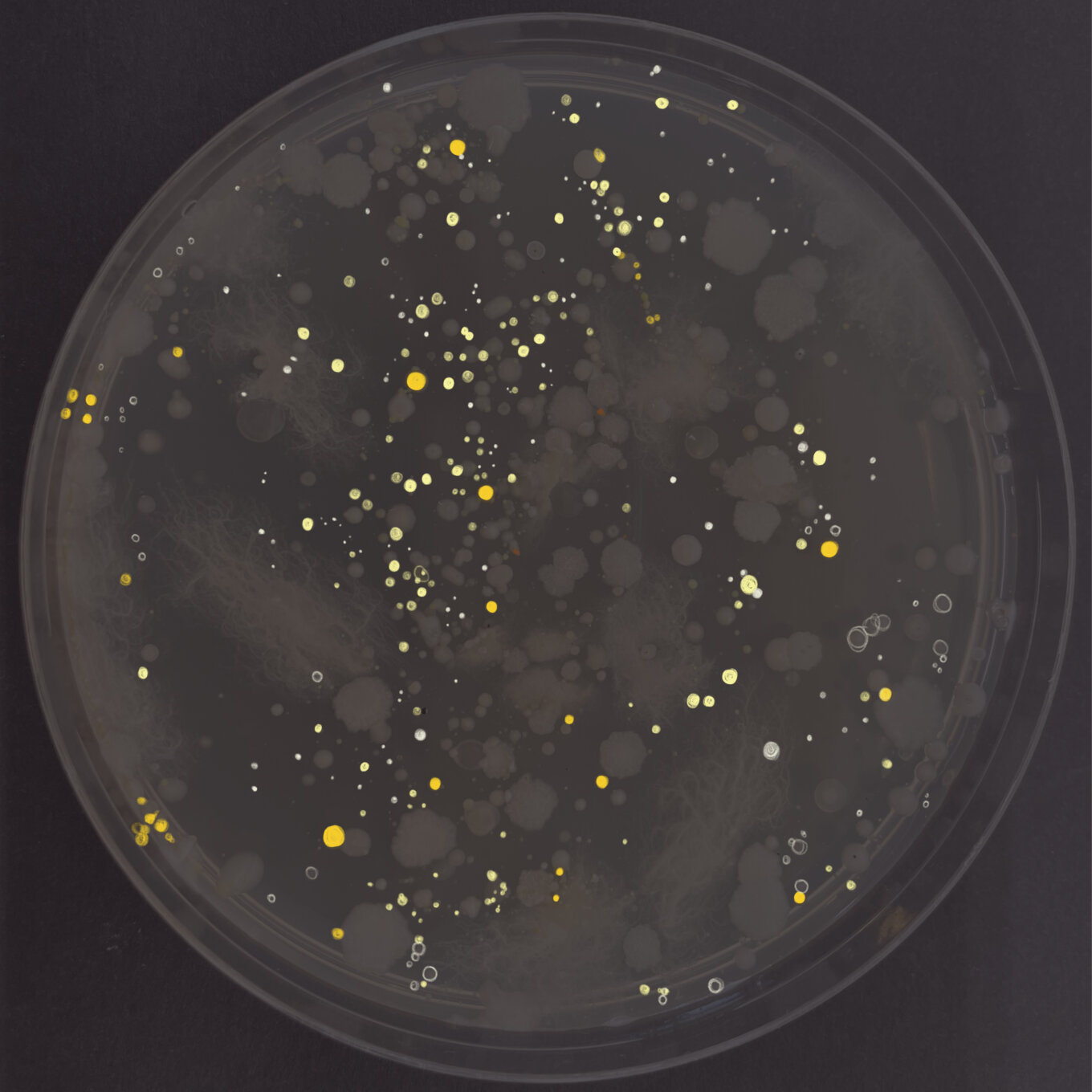

Sheffield Hallam University.Attempts to reveal coal mine pollution in Sheffield’s rivers led to a boundary-breaking collaboration for the City of Rivers exhibition.

Minewater is a common pollutant in Sheffield. It’s created by rainwater flowing through abandoned coal mines, pulling out metals and then depositing them in rivers and soils. This metal is mainly iron, giving minewater pollution a distinctive orange-rusty colour. High levels of metals alter the populations of bacteria, and may increase the amount of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the surrounding environment.

The Minewater Project is a Sheffield Hallam Blue Spaces Network collaboration which brought together artist Catherine Higham, environmental chemist Rachel Schwartz-Narbonne and microbiologist Mel Lacey.

The group took samples from a spring at Hollow Meadows in Rivelin Valley and analysed them in Sheffield Hallam University research laboratories. Catherine visited the lab as Mel and Rachel were studying the impact of minewater on the antibiotic resistance of soil bacteria, and developed a series of drawings responding to the experience.

This project has been selected as part of the City of Rivers exhibition at Weston Park Museum, which showcases the many ways rivers shape the city and the life within it. This artistic and scientific collaboration reveals the connections between waterways, humans, and other lifeforms. Catherine, Mel and Rachel spoke about how this cross-disciplinary collaboration came about for Now Then.

Mel: The idea of collaborating with an artist had been rattling around in my head for a while before I spoke to either of you. Science and art are often portrayed as opposites, with science being vigorous and fixed in its mindset and art being creative and free. From my own experience of microbiology, I knew this binary view didn’t show the whole picture – I knew science to be creative and beautiful. I was, and still am, fascinated by art and science’s shared ability to record the transient.

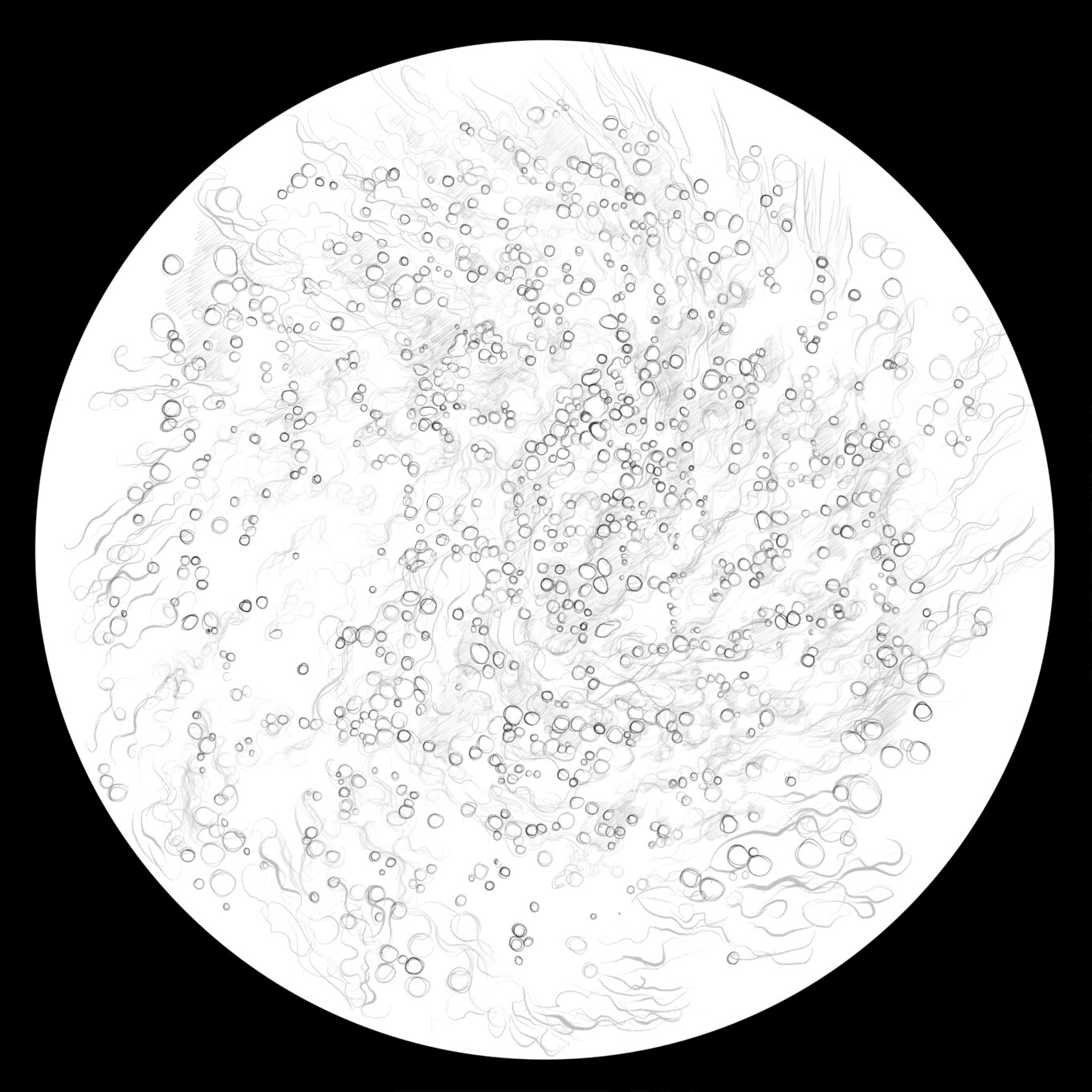

One of the pieces created as a result of the project.

Catherine Higham.Catherine: Although I immediately jumped at the invite to collaborate with you I had some initial trepidation, microbiology being a completely alien field! But I have an ongoing interest in space and astronomy, considering the macro-scale and the infinite, so taking ideas to the opposite end of the spectrum, to the microscopic, felt apt and really exciting.

Rachel: When you brought the idea to me I also fell in love with the project. As an environmental chemist I study pollutant molecules too small to see individually, so an artist was the perfect collaborator. Art and science both reveal hidden connections, using different methods to visualise the impact of pollution on the life within the river.

Catherine: The day’s residency in the lab enabled me to observe your methods and materials and start thinking about how the transient nature of this particular science could be responded to and investigated via art. While in the lab, what was really interesting was how the repetitive actions of the microbiology-based lab processes were akin to artistic methods of production. The honing of craft – a skill in a specific method or medium – as an artist is often a slow and iterative process that allows an artist to explore and convey ideas.

Mel: Equally, those repetitive processes are what allow us as scientists to ensure our work is reproducible and allow our results to be compared to others.

Catherine: In response to my experience in the lab, I made a series of digital drawings which are exported as time-lapse videos, showing how the work builds up or ‘grows’ over time. The drawings explore a new visual vocabulary; complex microscopic patterns and rhythms created by the bacteria as well as responding to the scientific methods and equipment used to record and develop them.

Mel: And I am obsessed with what you have created. Your drawings capture the essence of the bacteria we grew, in a way that is more than just a photograph ever could.

Catherine and Mel in front of their display at the City of Rivers exhibition.

Catherine: I think in drawing you can distil the essence of an idea or process in a way that’s impossible in a photographic snapshot. The hand-brain connection with drawing allows you to think through making – a drawing always leads to another drawing, or ideas for another piece of work.

Mel: The project was first exhibited at the Millennium Gallery in 2022 as part of their Live Late series, an annual art-science blended evening event of various themes.

Rachel: I love doing the Live Lates every year – distilling research into a fun, creative night which gives people a new perspective on science. There’s no point doing scientific research if we only ever speak to other scientists and never to the people who are affected by the environment we study. But we can’t use only the language of science when we’re speaking to non-scientists. Catherine’s art was a beautiful translator.

Catherine: The initial drawings were projected as large-scale animations on the gallery wall during the event, above a workstation where we invited the public to discuss the project and experiment with both lab and drawing equipment.

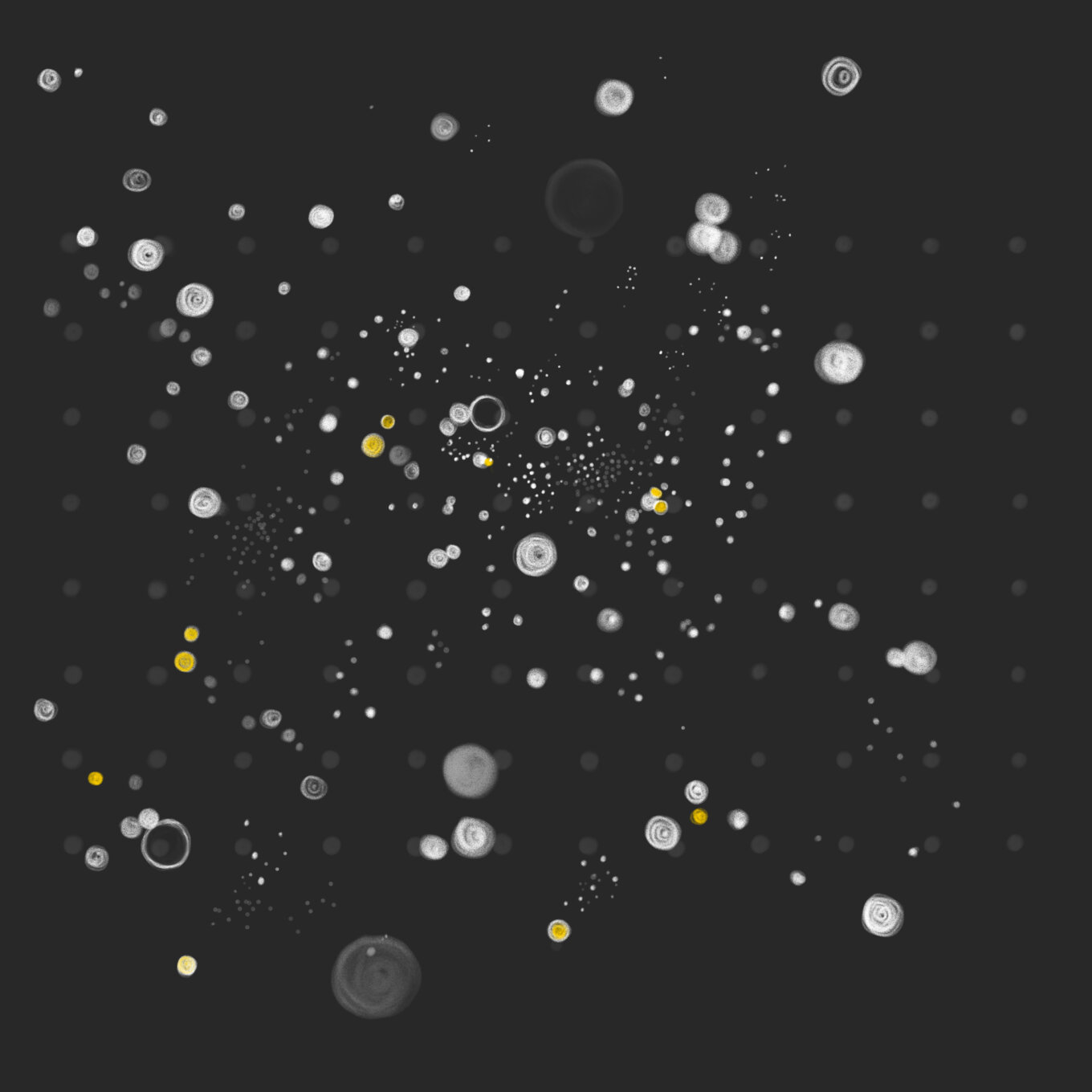

One of the pieces created as a result of the project.

Catherine Higham.Mel: When Sheffield Museums were planning the City of Rivers exhibition, they put out a call for pieces based around Sheffield and its rivers. We responded to this call and were the other side of excited when we found out our work was going to be part of the show.

Rachel: Since moving from Canada to the north of England, and to Sheffield specifically, I’ve come to really appreciate the strong identity in this part of the country. When we designed this project, it was grounded in the city’s industrial history and natural heritage of living rivers. We wanted to use our scientific voice to highlight where we live and to draw attention to the effects of pollution in our rivers.

Mel:

One of the things I think is impactful about our piece is the lack of

bacteria. We couldn’t keep the bacteria that grew in the lab alive

long enough to show them to the public, but this transient nature of

bacteria was the starting point of the project. I really like how the

bacteria are entirely shown in the art, with the science elements

being the tools we used to grow them.

Catherine: I like that too. The simplicity and what you leave out is as important as what’s included. In this exhibition at Weston Park Museum, the drawings are shown as still, printed images on the wall – a moment in time during the process of making them. The glass cabinet beneath the drawings displays the everyday lab equipment as precious museum specimens.

Rachel: I love working across disciplines, whether that’s

combining microbiology and chemistry or science and art. The further

I get from my ‘home’ field of chemistry, the harder it can be to

communicate, but the more magical it feels when I succeed and engage

in a new method of discovery. There’s so much to learn this way!

One of the pieces created as a result of the project.

Catherine Higham.Mel: This project has really impacted how I think about my work. Within science research we generally engage with artists at the end of a project, as a way of sharing our results with the public. I found real value in the difference of thought that working with Catherine gave, and I’ll endeavour to embed art throughout my research as a way to bring different perspectives and thought processes to complex problems.

Catherine: The project has underlined to me the importance of rigour – both in science and art. For art to be good art, it must be rigorous in its making and thinking. This process, what you learn from it, and what it leads to next are more important than the end result. Being open to and engaging with ideas from disciplines outside your own field is crucial. Science and art both challenge ideas and accepted wisdom, and move forward often without knowing what’s ahead. Being out of my comfort zone and involved in discussions and practices often beyond my level of understanding was hugely invigorating. I’m really looking forward to our next collaboration, whatever that may be.