Dig Where You Stand: “I'm not scared of being tired”: Désirée Reynolds and archival justice

Witnessing Dig Where You Stand, a new series that follows an archival justice movement that uncovers invisibilised histories of Sheffield

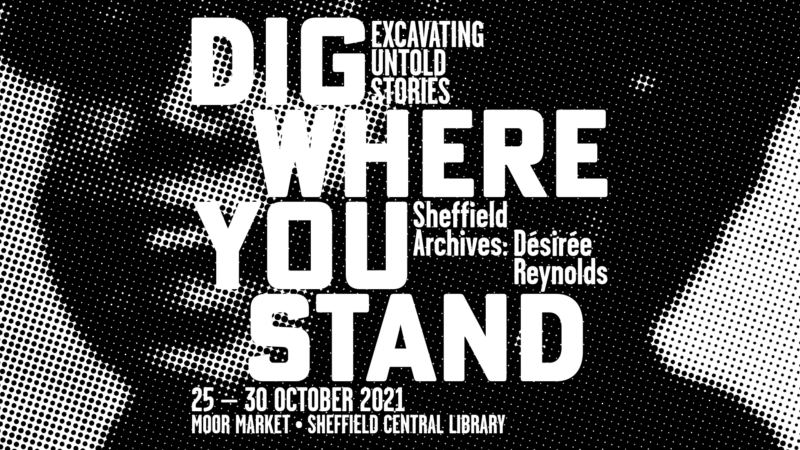

Dig Where You Stand (DWYS) is a project familiar to Now Then Magazine. Writer Désirée Reynolds leads the project alongside Sheffield Archive’s Cheryl Bailey and the Centre of Equity and Inclusion’s (CEI) Alex Rajinder Mason. Désirée has been the Writer in Residence at Sheffield Archives for some months, and now DWYS has been awarded £112,100 by the National Lottery Heritage fund.

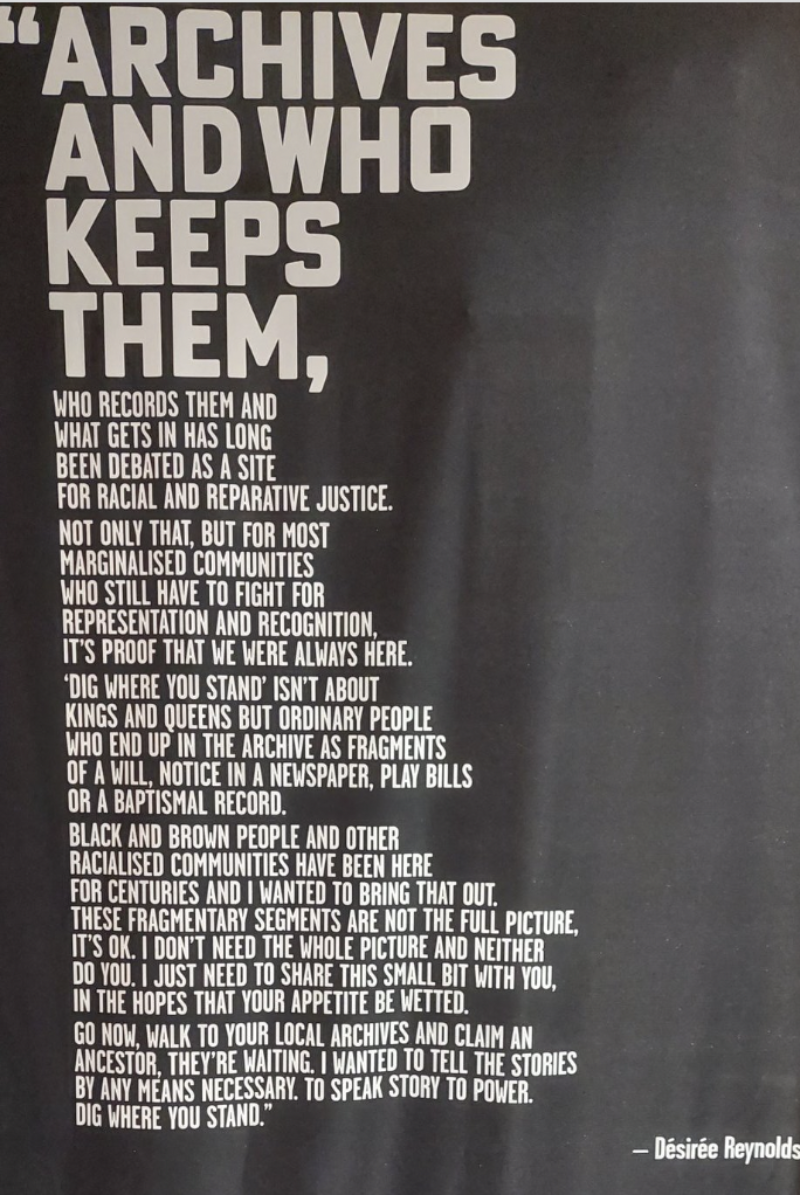

Fundamentally, DWYS seeks to unearth information on racially marginalised people in Sheffield. As the CEI description states:

Our mission is to address the harm and erasure endured by racially marginalised groups in historical processes. We do this by unearthing the untold stories of people of colour who have lived, worked and put down roots in South Yorkshire over hundreds of years. We also support people of colour to access archival records and use creative practices to reimagine the lives contained within them.

DWYS have commissioned 12 artists to display their work after engaging with the archive. It’s a radical project, especially for South Yorkshire and the north of England as a whole, that speaks to the work of historians like Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe, and Hortense Spillers. Each of these Black feminists have built bodies of work around careful recovery and re-narrativisation, as well as tender hospicing of Black cultural and social history.

I’ll be following DWYS’s exciting work during this latest iteration in order to highlight the process of Désirée, Cheryl, and Alex’s work. Often, writers and readers of Now Then Magazine alike will experience cultural events in Sheffield with great care and attention to the presentation of a culmination of art. With this series, however, I want to illuminate and witness the types of work that go into a project as rigorous and demanding as this one. I’ll attend workshops and trainings run by DWYS, speak to the creators and artists, and offer thoughts on how the project moves and changes during its funding period.

My own thoughts on witnessing are heavily influenced by James Baldwin’s seminal work on the topic. Baldwin often described himself as a witness, saying that he was “a witness to whence I came, where I am. Witness to what I’ve seen and the possibilities that I think I see.” In many ways, this series will be an exploration of Baldwin’s treatment of witnessing and, in continuing times of white supremacy, anti-Black terror, and ever-morphing racism, a delineation of the difference between spectating and witnessing. For Baldwin, witnessing is an active act of engagement and a purposeful writing-in of the author alongside art and culture. In other words, my engagements with DWYS are an exploration of our current political and cultural moments, of my own entanglements, and my interpretations of the people running DWYS.

I spoke to Désirée, writer, archivist, and visionary, about her thoughts going into the current phase of DWYS. It was a conversation full of laughter, knowing nods, and exploration of what might be ‘work,’ and what might be ‘life.’

Funding

As ever, witnessing in an era of neoliberal capitalism soon comes up against the question of funding. Désirée brought up one element of applying for, gaining, and managing funding bids. For those who aren’t familiar with such processes, particularly in relation to anti-racist projects, there can be many hoops to jump through, and much translation of goals into funder-friendly language.

Désirée told me how she’s often “educating people and, more exhaustingly, organisations about their approach and language and practice before even getting to the funding bit. Our job is not to educate anybody for a start, right? But somehow, engaging with these white cultural institutions, this is where we have to start, we have to educate them.”

Lankelly Chase, a major funding body, have just announced that they don’t want to work in a colonial way anymore. In a statement, they said:

We have recognised the gravity of the interlocking social, climate and economic global crises we are experiencing today. At the same time, we view the traditional philanthropy model as so entangled with colonial capitalism that it inevitably continues the harms of the past into the present.

It’s a rare move from UK funders, and whilst it remains to be seen exactly how Lankelly Chase will go about abolishing itself, it perfectly illustrates the colonialist and hostile environment Désirée describes. Désirée wondered if Lankelly Chase had thrown in the proverbial towel, saying, “I wondered whether working equitably was so hard that they thought, ‘Nah, I'm not doing it.”

“That they’ve chosen to abolish themselves speaks to how difficult it is. If a massive body with a lot of income has said they can’t do it, then what do other bodies make of that? How do you square that with entrenched power who doesn’t want to do the work in the first place? Well, we live in this society. And it will be interesting to find out who and how they’re giving away the money to, and in what time frame.

“It's the difference between giving away money and giving somebody tools, isn't it? And what does ‘giving' even mean? Notions of giving are part of the problem. So, it will be very interesting to see what happens and in what way those tools will be distributed and how they free up resources.”

Regardless of how Lankelly Chase goes about divesting their remaining funds, Désirée makes an interesting point. Handing money out is not the same as equipping people with structural tools that tackle systemic problems.

It’s difficult not to be reminded of George Floyd’s murder and the scramble for funders to give away huge amounts of money to organisations run by and for Black people. When the heat for white people died down and Black death was no longer in vogue, those same funders abandoned Black organisations and communities as they returned to business as usual. Désirée adds, “I think we are at a point where those organisations, funders, and charities engaging with marginalised groups still don’t know how to engage with us. That’s exactly why we’re continuously in teacher mode.”

An image of a table laden with spices, smells, and welcome cards. In the background, people engage with a Dig Where You Stand workshop at Sheffield Archives

Slippage

Once funding is secured, there’s the issue of the work itself.

Now, I wouldn't go so far as to say something is lost, but there is perhaps some slippage in taking in the culmination of a years-long project, and being the colleague or loved one of someone who has worked on said project. In this context, I’m thinking of anti-racist projects that often involve the identities of the people doing the work. I’ve worked – and still work – on plenty of projects that require me to engage my whole self, to foreground my lived experience of gender, race, sexuality, class, alongside my skills in anti-racist work. It’s not possible for there to be as clean a separation between my life and work, because I don’t have the privilege of doing so. Whilst I have no doubt that DWYS will be a roaring success, I would like to pick up points of discomfort or difficulty that are part and parcel of anti-racist work.

Désirée tells me, “It's tricky, isn't it? And it's hard to keep yourself whole. And I very rarely do it. Maryam, I'm telling you, if it wasn't for Alex [from CEI], I will, on a regular basis, bite the hand that feeds me. I'm very stubborn. And I'm a bit like, well, if you don't want it, I don't care.” Désirée’s stubborn refusal to live and die by funding appears to me to be an important intangibility with funders: funders can be communicated with, but funder-speak cannot, and should not, subsume the project.

Désirée continues, “I've got another thing that protects me – my children. I have two children. They're both neurodiverse as well. That peace that I have to bring to them has to be protected. Although, it's a process.” Désirée describes the push and pull between herself and Alex that provides a balance of sorts; she sees herself as reined in by Alex’s familiarity and expertise with funding requirements as nicely balanced by her self-sufficiency and creativity.

Désirée goes on to explain that the longevity of cultural and funding institutions can become a barrier to the delicate balance required of funded arts work. She says, “I do think that cultural institutions in particular are fully aware of their harmful practices. One example is, I think, everybody that runs them is there for far too long. I don't think you can be there for 30, 40 years and not submit yourself to constant retraining and constant reevaluation, and still be able to provide something that's useful for communities.” After all, Désirée says, “communities move at a rate of knots and if they’re still there thinking that the same thing that they did 20 years ago should be all right. That's mad to me.”

Gentleness and balance

During the last 10 years that I’ve spent researching and writing about anti-racism, people always want to know about how to protect yourself when the systems you write about are trying to destroy you and your communities. It’s difficult to think of funders as sometimes little more than sentient barriers who require translation into white coherency. A project like DWYS has so many tendrils of home, belonging, and memory. How does Désirée navigate the weight of her work, and the balance between work and life?

“I don't think I can separate it from myself. As much as I probably should do or want to, but it's also, because I am who I am. Within this trifecta of me and Alex and Cheryl – Alex is funding, academia, structure, lists, clear stuff that we've got that needs to be done. Cheryl is the actual keeper of the information. She's amazing with what she can keep in the head, which is what archivists do, right? But she also is a powerful co-conspirator, a working class woman who herself has to navigate the systems that seek to ignore her expertise. I think I sit in between them both, kind of drawing their disciplines together, if you like. So, knowing that, I find it incredibly stressful, and exhausting, and terrifying and exciting. And what if I mess up? But I'm not scared of it. I'm not scared of being tired. I've got family, I live here, I’m a Black woman, engaging with art spaces, ha! I'm tired every day.”

Whilst self-care, or at least the performance of it, is fashionable, as Désirée says, there is a “commodification of wellness and self care that makes me feel a bit icky.”

She instead thinks that the basic tenets of care have been the same for some time: “family, food, communion, community, nature. All the things that you use to recharge yourself have actually probably been the same since time immemorial, isn't it? But somehow it's been commodified. It's a bit worrying. I know we sometimes need help with a reconnection with ourselves and things outside of us, it’s those things that are the same.” But, as Désirée explains, this all depends on her work pattern. “The things that I do to keep myself well is that I don't. I work, work, work, crash, work, work, work, crash, work, crash, and then in those crashy moments, I chat to my friends and family and I go off and sit somewhere in the woods, dangle my feet in some water, read. I'm a workaholic. I live in the work and the work in this instance is visibility.”

It’s refreshing to hear someone speak about the impulse to work, and how to see that a crash is inevitable. Of course, no one is saying this is ideal, but it’s a truthful reflection of the weight of this type of work. And that weight is something which is difficult to communicate to funders.

And there, precisely, is where I’d like to locate my series on DWYS. Maybe the question shouldn’t be how to maintain a work-life balance, but instead how to curate calm amongst the crashings of death that threaten to drown those who do anti-racist work. The artists and archivists involved in DWYS will undoubtedly be faced with heartbreaking and violent histories that nobody else has bothered to uncover. That’s not something which can be put down easily or quickly.

Perhaps it’s time to stop asking individuals how they can care for themselves in fundamentally violent systems, and instead to fully witness the how and why of those same systems, in order to better untangle care for those in our communities.