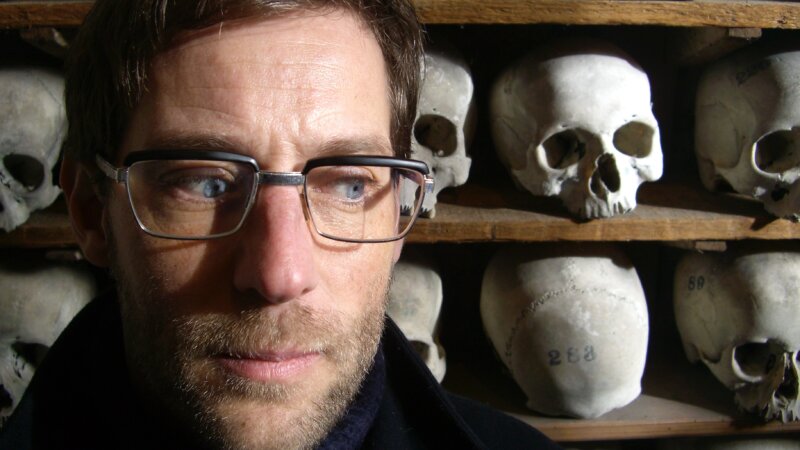

Jason Singh: The Singh Thing

"I never, ever had the ambition to be a musician," insists Jason Singh, who now finds himself in the enviable position of being able to handpick the musical projects he follows - from touring India with a mouth harpist named Rais Khan to a new band named Open Souls with Polar Bear drummer Seb Rochford, via other collaborations with jazz saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings and with Soumik Datta, a sarod player based in London.

It all began with a simple desire to play music for its own sake, growing up near London's Brick Lane during the 1980s. "I've always had an extreme passion for rhythm and sound - it's usually been beats, then sound and patterns within sound - that's from an early age, two or three years old. Then later on, the kids I grew up with - everybody beatboxed, but nobody said it was beatboxing. We just all made sounds."

It isn't a skill that many have pursued and developed with the same dedication as Singh, so it's no wonder that he's in demand. His is a rare ability; fine-tuned to vocalise from the most delicate of pin-drop sounds to seemingly uncontrolled, foundation-rumbling basslines. Only seemingly, because he aims to remain in control for the majority of his performances. "Ninety per cent of my practice is without technology. I've seen so many beatboxers who're set to fail because their set is based around technology." Singh labels himself a beatboxer and vocal sculptor. Neither are truly satisfactory descriptions, but they do succeed in illustrating the vast distance between musical styles he has covered during his time recording and performing music.

At one end of the spectrum there is Singh's solo beatboxing, which began in earnest as filler between performers at a night called Spellbound at Band On The Wall in Manchester. He'd moved to Stretford in 1993 and a few years later was playing percussion with a band named Nashini, taking the mic during intervals to perform snappy skits.

But the breakthrough moment arose from journalism and teaching work, specifically during a trip to Australia where he performed an impromptu gig with Nitin Sawhney, whom he'd met in another capacity as a fledgling journalist for publications such as City Life. "I would do interviews with Nitin, but he never really knew me as a musician. So when he heard me beatboxing at this workshop we did in Australia, he was like 'Oh I didn't know you were a muso!' I was doing turntable cuts then I dropped some beats and he asked if I wanted to do a gig, so it sort of escalated from there."

Singh's most impassioned replies involve his roles as pedagogue for the next generation. From DJing and beatboxing workshops at the Contact Theatre around the turn of the millennium to a workshop set to realign "what jazz is and what people perceive it to be" at last month's London Jazz Festival, Singh's core motivation is to pass on the fruits of his varied explorations. "There's been no plan or strategy behind any of this," he reminds me. "But the education side is paramount to what I do because for me experience is pointless just to hold onto and only share through performance.

"I did a three day workshop in India a couple of years ago, working with two young lads who were interested in learning beatboxing techniques. They've gone onto set up a group called Boxy Turvy, performed on MTV, done stuff with Shlomo. I think they're part of his Vocal Orchestra now.

"And this is the thing - you don't know where this stuff goes. You can inspire someone at a gig or when they buy your music, but when you inspire somebody through education it's a completely different thing because so many kids are told they can't do that or they shouldn't do that or play your fucking Xbox, as opposed to doing something a bit more creative."

Therein lies the distinction Jason tries to make between the ambition to be a musician and instead making music as part of an exploration of the world around him. London's Victoria and Albert Museum picked up on this after he applied to their Supersonic residency programme. "That was an amazing opportunity. A lot of my work through education had finished, so I applied and you had to propose a project, so I said well I'm really interested in vessels, my body as a vessel, architecture and sound and how sound is manipulated within these vessels, and that I was going to explore these relationships through the Middle Eastern collection and that I'm inspired a lot by Islamic and Sufi poetry. It was just tick, tick, tick for everything. They were like, 'That's brilliant! What do you want to do and how would you do it?'"

Other projects gained coverage on BBC4 documentary Imagine last year, which looked at The Lost Music of Rajasthan. One of the featured music organisations had established a seven-year project bringing together musicians in Rajasthan, with which Singh was involved. The filming period at the end of Rajasthan International Folk Festival marked the tail-end of those seven years, at which time Singh had just begun to make music with mouth harpist Rais Khan, their debut show being screened on the programme to illustrate the synchronicity of styles old and new. "We did this 20 minute slot and people went bonkers. They'd never heard the instrument in that context. So we're doing drum and bass and crazy dubstep lines - all with this little metal harp."

Singh's work with cinema shies away from that extreme and towards tranquillity, again highlighting the breadth of his musical spectrum. He may bemoan his prior luck with film score projects - many fizzled out before completion - but recently that luck has changed. "I've always had desires to make a vocal, beatboxing score to a film. I've picked films but it's always turned out that it's never happened."

A live set drawing on the Private Paradise exhibition at Whitworth Art Gallery in August 2011 displayed in full the potential multisensory appeal of his compositions. Soon after, Singh soundtracked a Quay Brothers film, Street Of Crocodiles, with violinist Olivia Moore as part of a Now Then show and he will take on a different short this year at Trof Fallowfield as part of Manchester's Shebeen Festival.

But his biggest film work came through The Cornerhouse's Micro Commissions scheme. Following tentative work on a BFI project in 2010 that was shelved, the BFI suggested he score a film they'd been planning to re-issue named Drifters, a 1929 John Grierson silent documentary about the impact of technology on the fishing industry. Ever the teacher, even Singh was taken by surprise with how revered the film is. "When I performed it at the Cornerhouse, all these film students turned up and asked me all about John Grierson - and I shit myself! I never went into it researching John Grierson. It was solely about the footage because I get freaked out by hype, so I try to focus just on the material I'm working with, regardless of its history or its previous interpretations. It's like: there's the work, that's what I'm gonna do. This guy at the end was like, 'I worked with John Grierson... and he would've loved this.' It was mad; absolutely insane."

thesinghthing.com )